From the 1830’s onward, German research universities enjoyed a considerable international reputation, whereas most modern historians agree that the French university system had fallen into a period of neglect during the Second Empire (i.e. Collins 2005, Kelly 2008, Wiesz 2014), with Georg Iggers the historian Georg Iggers writing that they were virtually “moribund” (Iggers 2011). This educational “reform movement” though perhaps greatly needed, not unique to France. Calls to echo the German university system were being made in a number of countries, including the United States, Italy, across Scandinavia (Collins ibid.).

By 1860, writes Weisz, academia had become increasingly critical of the status and condition of their profession, yet this dissatisfaction as likely had a second face, an increasing resistance to the Louis Napoleon. The Empire had founded its legitimacy with estimated 26,000 arrests, relocations, and deportations, (Davis 2004) and the institutionalization a police surveillance state; and it was within this decade that academics became “acutely aware of their vulnerability” (Weisz ibid.) and their lack of their importance to the Napoleon government. But, over the years, as Napoleon gradually began to lessen the pressure he applied to the heel of his boot, as widespread discontent to fester, effectively, in horizontal dissent. While prison was still the destination for those critical of the regime, indirect criticism of subsidiary institutions did appear to be tolerated. It was during this period that scholars, having had professional exchanges with German academicians, saw the enhanced prestige the Germans enjoyed and world-class estimation of German universities, while witnessing their own prestige slipping. Weisz writes professors sought to improve their social position, their pay, and the international standing. With the sliver of freedom accorded by the relaxation of the police state, the liberal Republicans and “Radicals” who considered themselves the “inheritors of the Jacobin tradition”(Conklin, Fishman, Zaretsky 2015) were able to raise criticisms of the government. The demanded reforms to one of Napoleon’s subsidiary institutions, the de-centralization of higher education.

In the 1860’s this dissent showed itself in opposition to the system of education centralization may have been viewed as an imperative to the betterment of the university system, but centralization was equally a condemnation of Louis Napoleon’s autocratic leadership style. Weisz writes that centralization became such a touchstone that many French attributed “excessive centralization to the ills of French society” (Weisz 2010).

Just as liberal academicians were blaming centralization for a variety of woes, Louis Napoleon, who was facing difficulties with clergy, felt forced to turn to a dissatisfied academic community for support (Weisz ibid.). The biggest move in this direction was to appoint the liberal historian, Victor Duruy, as his education minister. Isabel Noronha-DiVanna writes that Duruy “instituted an ambitious process of modernization” between his appointment in 1863 and leaving the position 1869 (Noronha-DiVanna 2010). However, Weisz is far more detailed, writing that Duruy worked to decentralize his educational administration to allow for greater autonomy for rectors to make decisions at the local level, but “his more ambitious reform projects failed to be executed”(Weisz ibid).

Following the capitulation of the Empire, many of the most active in calling for university reform, ironically were not academicians who had gained their agrégation and worked within the universities themselves, but rather historians who had gained their “eminence” as writers and researchers. Duruy had been of this camp, as well as Hippolyte Taine and Ernest Renan, and many more were historians who were already receiving historical influence from Neihbor, Ranke, where “common Frankish and Carolingian past together (Kelley 2008).

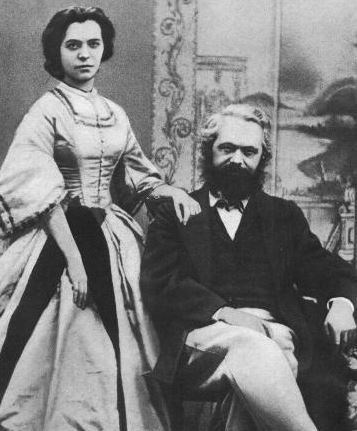

When the ‘scientific’ methodologies of the Berlin school, which are so closely identified with German academia, began to develop in the early 19th-century, the historical field had been dominated by two competing approaches: nationalistic romanticism and Hegelianism. Romanticism, the romanticization of historical accounts, such as nationalistic telling of the conquests of military leaders, much to the Berliner’s consternation had still been considered a legitimate form of history, while the Hegelian school applied the structure of 18th-religious teleology, in which believed that God was be found in man’s purpose, man’s goals, and man’s destiny. Hegel replaced God in this structural equation with the events of history, believing that the results of history could be explained by man’s actions. It should be noted that Marx’s theory of history was built on this premise.

The methodological Berlin school rejected both the romanticists and philosophical approaches as deeply flawed, and instead focused upon empirical data from primary sources. Their movement was absolutely moving the field of history forward, in keeping with the scientific method which was dramatically and quickly changing the known world. By 1850, Hegelian If Ranke was the father of scientific methodology, he had an active and very able cadre in Barthold Georg Niebuhr, Friedrich Nietzche, and Mommsen.

Whatever the consternation that “the French intellectual status within the academic community was on the wane” (Weisz 2014). Some and that the enemy across the Rhine was outpacing them in the study of history, as many a modern historian has written (ie. Noronha-DiVanna 2010), the French historian, Fustel de Coulanges, had been moving in this empirical, scientific direction since at least 1862. In his inaugural lecture at the University de Strasbourg in 1862, he said, “History is and should be a science… “for the study of man, is man himself. “Man, who to be wholly known, requires several sciences for himself.” In the same speech, de Coulanges, in a precursor the Annalistes’ notion of the longue durée, lectured: “History, I think, fulfills its task only when it covers a series of centuries. If one restricts ones study to a limited period, one can tell a story full of antidotes and details with will satisfy the curiosity and occasionally amuse… but I find it difficult to convince myself that it would be true history” (de Coulanges 1862 transcript, Stern 2011)

In the early 1800’s, romanticist histories and philosophical arguments dominated the historical field, but a new historical approach referred to as the “Berlin school,” which was led by Leopold von Ranke (1775-1886) and supported by the intellectual giants. Reinhold Niebuhr and Fredrick Nietzche, was beginning to dominate historical study. Outgoing and increasingly discredited by the 1870’s were the romanticist historians whose accounts glorified rulers like Napoleon and Frederick the Great, while wonderfully patriotic, were increasingly considered to be unfaithful to the truth. The Hegelians, although contemporaries of the romanticists, were a far more legitimate school of thought by 1870. For Hegelians, a school of thought which greatly influenced Marx, there was an underlying purpose or system which lies behind how history evolves, that in a grand systematic design, actions could be explained by their results. These ideas carried the loose structure the 18th-century teleology, that God could be found in man’s purpose, his goals, and his destiny. The Berlin school was hyper-critical of this philosophical, almost metaphysical approach to history. According to Anthony Jensen, the Berliner’s derided Hegelians “speculation, their uncritical method, their willy-nilly dependence on milquetoast generalizations… [and the worst transgression was] the global imposition of a philosophical system upon the raw facts of the past” (Jensen 2016). The work by Leopold von Ranke was, at that time, considered the cutting edge of “scientific” history. Ranke utilized primary (empirical) archival-research and applying specific methodologies. In what these historians felt was in keeping with the scientific method, historical inquiry would now focus on archival accounts which could reliably be established as true through source comparison.

Donald Kelley writes that there was already a cross-pollination of ideas across the Rhine, with German scholars living in Paris to work in the libraries, and French students traveling to Berlin and Göttingen, as Charles Seignobos did for two years (probably a little before 1879 when he took a position at the Université de Bourgogne (Wikipedia)). The commonality that the historians of France and Germany had in medieval studies naturally drew these scholars together despite their conflicting methods and philosophies (Kelly 2008).

Yet, Georg Iggers writes that Seignobos, who had studied in Germany, was “highly critical of the German tradition and considered Ranke outdated,” citing Seignobos and Langlois 1898 book, the Introduction to the Study of History (Iggers ibid.). I’m not in full agreement with Iggers here. Indeed, the Seignobos and Langlois did make a general statement regarding Ranke, but it was more of a generalization that they considered scholars of only a few years past to now be outdated. The professionalization of history was moving at a rapid pace, and Seignobos and Langlois were including both French and Germans in this melange of obsolete thought. The pair wrote “Augustin Thierry, Ranke, Fustel de Coulanges, Taine, and others, are already battered and riddled with criticism. The faults of their methods have already been seen, defined, and condemned” (Seignobos, Langlois 1898).

Further, quite a bit of water had flowed under the historical bridge from the time when Seignobos had studied in Berlin in the 1870’s and the turn of the century when Langlois and Seignobos wrote Introduction à l’étude de l’histoire. At the time of Introduction’s publishing, Seignobos was already six years into his decade-long series of debates with the father of sociology, Émile Durkheim.

Following the defeat at the hands of the Germans, the French historians who were pursuing methodological history became sensitive to mounting criticisms that their work amounted to the Germanification of French historical study. In response, the French scholars increased the purity of the positivism in French human sciences (Noronha-DiVanna 2010). In essence, Seignobos et al. sought to out-science the Germans whom they mirrored. To this end, Iggers writes that Seignobos’ ideas had become “fundamentally different from [Ranke’s] neo-Kantian understanding of history,” and that the French methologists had rejected the humanities inherent in the German intellectual concept of Geisteswissenschaften (Iggers, 2011). Geisteswissenschaften, which has its roots in Hegel’s Volksgeist, is an integral part the German academic approach, the holistic approach to the study of humanities, involving literature, history, sociology, language studies, and music. Much as the Germans viewed “history as part of the social sciences,” (Iggers, ibid.), it would be Durkheim who injected into the French academic world that history was elemental to sociology and sociology to history. This was a problem for Seignobos and the French historical methodologists, who, having distanced themselves from German Geisteswissenschaften in the 1870 and 1880’s, found themselves unable to accept the historical-sociological connections linked by Durkheim twenty five years later.

Click here to return to the main article.

Sources:

France and Its Empire Since 1870, Alice L. Conklin, Sarah Fishman, Robert Zaretsky, Oxford University Press, 2015

An Interpretation of Nietzsche’s “On the Uses and Disadvantages of History, Anthony K. Jensen, Routledge, 2016

The Emergence of Modern Universities In France, 1863-1914, George Weisz, Princeton University Press, 2014

Fortunes of History: Historical Inquiry from Herder to Huizinga, Donald R. Kelley, Yale University Press, 2008

The intellectual Foundations of the Nineteenth-Century “Scientific’ History: The German Model, Georg G. Iggers, undated, The Oxford History of Historical Writing: Volume 4: 1800-1945, Stuart Macintyre, Daniel R. Woolf, Andrew Feldherr, Grant Hardy, OUP Oxford, Oct 27, 2011

Ethos of a Scientific Historian Fustel de Coulanges, lecture 1862, translated by Fritz Stern, The Varieties of History: From Voltaire to the Present, Fritz Stern, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011

Writing History in the Third Republic, Isabel Noronha-DiVanna Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2010

Introduction to the Study of History, Charles V. Langlois and Charles Seignobos, Henry Holt and Company, 1904, digitized by The Project Gutenberg, 2009

In 1845 Marx and Engels wrote that man’s first social organizations were to work together for tribal food production (Marx,

In 1845 Marx and Engels wrote that man’s first social organizations were to work together for tribal food production (Marx,